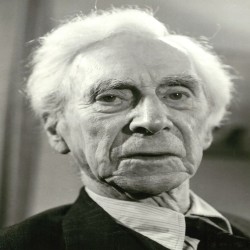

Bertrand Russell

British mathematician and philosopher

| Date of Birth | : | 18 May, 1872 |

| Date of Death | : | 21 Feb, 1979 |

| Place of Birth | : | Trelleck, United Kingdom |

| Profession | : | Mathematician, Philosopher |

| Nationality | : | American |

Bertrand Russell (born May 18, 1872, Trelleck, Monmouthshire, Wales—died February 2, 1970, Penrhyndeudraeth, Merioneth) British philosopher, logician, and social reformer, founding figure in the analytic movement in Anglo-American philosophy, and recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950. Russell’s contributions to logic, epistemology, and the philosophy of mathematics established him as one of the foremost philosophers of the 20th century. To the general public, however, he was best known as a campaigner for peace and as a popular writer on social, political, and moral subjects. During a long, productive, and often turbulent life, he published more than 70 books and about 2,000 articles, married four times, became involved in innumerable public controversies, and was honoured and reviled in almost equal measure throughout the world. Russell’s article on the philosophical consequences of relativity appeared in the 13th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica.

Russell was born in Ravenscroft, the country home of his parents, Lord and Lady Amberley. His grandfather, Lord John Russell, was the youngest son of the 6th Duke of Bedford. In 1861, after a long and distinguished political career in which he served twice as prime minister, Lord Russell was ennobled by Queen Victoria, becoming the 1st Earl Russell. Bertrand Russell became the 3rd Earl Russell in 1931, after his elder brother, Frank, died childless.

Early Life

Inspired by the work of the mathematicians whom he so greatly admired, Russell conceived the idea of demonstrating that mathematics not only had logically rigorous foundations but also that it was in its entirety nothing but logic. The philosophical case for this point of view—subsequently known as logicism—was stated at length in The Principles of Mathematics (1903). There Russell argued that the whole of mathematics could be derived from a few simple axioms that made no use of specifically mathematical notions, such as number and square root, but were rather confined to purely logical notions, such as proposition and class. In this way not only could the truths of mathematics be shown to be immune from doubt, they could also be freed from any taint of subjectivity, such as the subjectivity involved in Russell’s earlier Kantian view that geometry describes the structure of spatial intuition. Near the end of his work on The Principles of Mathematics, Russell discovered that he had been anticipated in his logicist philosophy of mathematics by the German mathematician Gottlob Frege, whose book The Foundations of Arithmetic (1884) contained, as Russell put it, “many things…which I believed I had invented.” Russell quickly added an appendix to his book that discussed Frege’s work, acknowledged Frege’s earlier discoveries, and explained the differences in their respective understandings of the nature of logic.

The tragedy of Russell’s intellectual life is that the deeper he thought about logic, the more his exalted conception of its significance came under threat. He himself described his philosophical development after The Principles of Mathematics as a “retreat from Pythagoras.” The first step in this retreat was his discovery of a contradiction—now known as Russell’s Paradox—at the very heart of the system of logic upon which he had hoped to build the whole of mathematics. The contradiction arises from the following considerations: Some classes are members of themselves (e.g., the class of all classes), and some are not (e.g., the class of all men), so we ought to be able to construct the class of all classes that are not members of themselves. But now, if we ask of this class “Is it a member of itself?” we become enmeshed in a contradiction. If it is, then it is not, and if it is not, then it is. This is rather like defining the village barber as “the man who shaves all those who do not shave themselves” and then asking whether the barber shaves himself or not.

At first this paradox seemed trivial, but the more Russell reflected upon it, the deeper the problem seemed, and eventually he was persuaded that there was something fundamentally wrong with the notion of class as he had understood it in The Principles of Mathematics. Frege saw the depth of the problem immediately. When Russell wrote to him to tell him of the paradox, Frege replied, “arithmetic totters.” The foundation upon which Frege and Russell had hoped to build mathematics had, it seemed, collapsed. Whereas Frege sank into a deep depression, Russell set about repairing the damage by attempting to construct a theory of logic immune to the paradox. Like a malignant cancerous growth, however, the contradiction reappeared in different guises whenever Russell thought that he had eliminated it.

Quotes

Total 24 Quotes

The first step in a fascist movement is the combination under an energetic leader of a number of men who possess more than the average share of leisure, brutality, and stupidity. The next step is to fascinate fools and muzzle the intelligent, by emotional excitement on the one hand and terrorism on the other.

My first advice (on how not to grow old) would be to choose you ancestors carefully.

The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, and wiser people so full of doubts.

If an opinion contrary to your own makes you angry, that is a sign that you are subconsciously aware of having no good reason for thinking as you do.

There have been poverty, pestilence, and famine, which were due to man's inadequate mastery of nature. There have been wars, oppressions and tortures which have been due to men's hostility to their fellow men.

Men are born ignorant, not stupid. They are made stupid by education.

We know too much and feel too little. At least, we feel too little of those creative emotions from which a good life springs.

If we spent half an hour every day in silent immobility, I am convinced that we should conduct all our affairs, personal, national, and international, far more sanely than we do at present.

None of our beliefs are quite true; all have at least a penumbra of vagueness and error.

Fear is the main source of superstition, and one of the main sources of cruelty. To conquer fear is the beginning of wisdom.