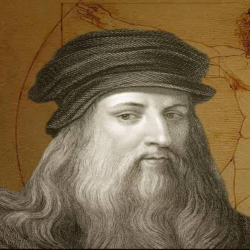

Leonardo da Vinci

Italian Writer and Polymath

| Date of Birth | : | 15 Apr, 1452 |

| Date of Death | : | 02 May, 1519 |

| Place of Birth | : | Anchiano, Italy |

| Profession | : | Painter, Writer, Polymath |

| Nationality | : | Italian |

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect.

Biography

The unique fame that Leonardo enjoyed in his lifetime and that, filtered by historical criticism, has remained undimmed to the present day rests largely on his unlimited desire for knowledge, which guided all his thinking and behaviour. An artist by disposition and endowment, he considered his eyes to be his main avenue to knowledge; to Leonardo, sight was man’s highest sense because it alone conveyed the facts of experience immediately, correctly, and with certainty. Hence, every phenomenon perceived became an object of knowledge, and saper vedere (“knowing how to see”) became the great theme of his studies. He applied his creativity to every realm in which graphic representation is used: he was a painter, sculptor, architect, and engineer. But he went even beyond that. He used his superb intellect, unusual powers of observation, and mastery of the art of drawing to study nature itself, a line of inquiry that allowed his dual pursuits of art and science to flourish.

Life and works

Leonardo’s parents were unmarried at the time of his birth. His father, Ser Piero, was a Florentine notary and landlord, and his mother, Caterina, was a young peasant woman who shortly thereafter married an artisan. Leonardo grew up on his father’s family’s estate, where he was treated as a “legitimate” son and received the usual elementary education of that day: reading, writing, and arithmetic. Leonardo did not seriously study Latin, the key language of traditional learning, until much later, when he acquired a working knowledge of it on his own. He also did not apply himself to higher mathematics—advanced geometry and arithmetic—until he was 30 years old, when he began to study it with diligent tenacity.

Leonardo’s artistic inclinations must have appeared early. When he was about 15, his father, who enjoyed a high reputation in the Florence community, apprenticed him to artist Andrea del Verrocchio. In Verrocchio’s renowned workshop Leonardo received a multifaceted training that included painting and sculpture as well as the technical-mechanical arts. He also worked in the next-door workshop of artist Antonio Pollaiuolo. In 1472 Leonardo was accepted into the painters’ guild of Florence, but he remained in his teacher’s workshop for five more years, after which time he worked independently in Florence until 1481. There are a great many superb extant pen and pencil drawings from this period, including many technical sketches—for example, pumps, military weapons, mechanical apparatus—that offer evidence of Leonardo’s interest in and knowledge of technical matters even at the outset of his career.

First Milanese period (1482–99)

In 1482 Leonardo moved to Milan to work in the service of the city’s duke—a surprising step when one realizes that the 30-year-old artist had just received his first substantial commissions from his native city of Florence: the unfinished panel painting Adoration of the Magi for the monastery of San Donato a Scopeto and an altar painting for the St. Bernard Chapel in the Palazzo della Signoria, which was never begun. That he gave up both projects seems to indicate that he had deeper reasons for leaving Florence. It may have been that the rather sophisticated spirit of Neoplatonism prevailing in the Florence of the Medici went against the grain of Leonardo’s experience-oriented mind and that the more strict, academic atmosphere of Milan attracted him. Moreover, he was no doubt enticed by Duke Ludovico Sforza’s brilliant court and the meaningful projects awaiting him there.

Leonardo spent 17 years in Milan, until Ludovico’s fall from power in 1499. He was listed in the register of the royal household as pictor et ingeniarius ducalis (“painter and engineer of the duke”). Leonardo’s gracious but reserved personality and elegant bearing were well-received in court circles. Highly esteemed, he was constantly kept busy as a painter and sculptor and as a designer of court festivals. He was also frequently consulted as a technical adviser in the fields of architecture, fortifications, and military matters, and he served as a hydraulic and mechanical engineer. As he would throughout his life, Leonardo set boundless goals for himself; if one traces the outlines of his work for this period, or for his life as a whole, one is tempted to call it a grandiose “unfinished symphony.”

As a painter, Leonardo completed six works in the 17 years in Milan. (According to contemporary sources, Leonardo was commissioned to create three more pictures, but these works have since disappeared or were never done.) From about 1483 to 1486, he worked on the altar painting The Virgin of the Rocks, a project that led to 10 years of litigation between the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception, which commissioned it, and Leonardo; for uncertain purposes, this legal dispute led Leonardo to create another version of the work in about 1508. During this first Milanese period he also made one of his most famous works, the monumental wall painting Last Supper (1495–98) in the refectory of the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie (for more analysis of this work, see below Last Supper). Also of note is the decorative ceiling painting (1498) he made for the Sala delle Asse in the Milan Castello Sforzesco.

During this period Leonardo worked on a grandiose sculptural project that seems to have been the real reason he was invited to Milan: a monumental equestrian statue in bronze to be erected in honour of Francesco Sforza, the founder of the Sforza dynasty. Leonardo devoted 12 years—with interruptions—to this task. In 1493 the clay model of the horse was put on public display on the occasion of the marriage of Emperor Maximilian to Bianca Maria Sforza, and preparations were made to cast the colossal figure, which was to be 16 feet (5 metres) high. But, because of the imminent danger of war, the metal, ready to be poured, was used to make cannons instead, causing the project to come to a halt. Ludovico’s fall in 1499 sealed the fate of this abortive undertaking, which was perhaps the grandest concept of a monument in the 15th century. The ensuing war left the clay model a heap of ruins.

As a master artist, Leonardo maintained an extensive workshop in Milan, employing apprentices and students. Among Leonardo’s pupils at this time were Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, Ambrogio de Predis, Bernardino de’ Conti, Francesco Napoletano, Andrea Solari, Marco d’Oggiono, and Salai. The role of most of these associates is unclear, leading to the question of Leonardo’s so-called apocryphal works, on which the master collaborated with his assistants. Scholars have been unable to agree in their attributions of these works.

Second Florentine period (1500–08) of Leonardo da Vinci

In December 1499 or, at the latest, January 1500—shortly after the victorious entry of the French into Milan—Leonardo left that city in the company of mathematician Lucas Pacioli. After visiting Mantua in February 1500, in March he proceeded to Venice, where the Signoria (governing council) sought his advice on how to ward off a threatened Turkish incursion in Friuli. Leonardo recommended that they prepare to flood the menaced region. From Venice he returned to Florence, where, after a long absence, he was received with acclaim and honoured as a renowned native son. In that same year he was appointed an architectural expert on a committee investigating damages to the foundation and structure of the church of San Francesco al Monte. A guest of the Servite order in the cloister of Santissima Annunziata, Leonardo seems to have been concentrating more on mathematical studies than painting, or so Isabella d’Este, who sought in vain to obtain a painting done by him, was informed by Fra Pietro Nuvolaria, her representative in Florence.

Perhaps because of his omnivorous appetite for life, Leonardo left Florence in the summer of 1502 to enter the service of Cesare Borgia as “senior military architect and general engineer.” Borgia, the notorious son of Pope Alexander VI, had, as commander in chief of the papal army, sought with unexampled ruthlessness to gain control of the Papal States of Romagna and the Marches. When he enlisted the services of Leonardo, he was at the peak of his power and, at age 27, was undoubtedly the most compelling and most feared person of his time. Leonardo, twice his age, must have been fascinated by his personality. For 10 months Leonardo traveled across the condottiere’s territories and surveyed them. In the course of his activity, he sketched some of the city plans and topographical maps, creating early examples of aspects of modern cartography. At the court of Cesare Borgia, Leonardo also met Niccolò Machiavelli, who was temporarily stationed there as a political observer for the city of Florence.

In the spring of 1503 Leonardo returned to Florence to make an expert survey of a project that attempted to divert the Arno River behind Pisa so that the city, then under siege by the Florentines, would be deprived of access to the sea. The plan proved unworkable, but Leonardo’s activity led him to consider a plan, first advanced in the 13th century, to build a large canal that would bypass the unnavigable stretch of the Arno and connect Florence by water with the sea. Leonardo developed his ideas in a series of studies; using his own panoramic views of the riverbank, which can be seen as landscape sketches of great artistic charm, and using exact measurements of the terrain, he produced a map in which the route of the canal (with its transit through the mountain pass of Serravalle) was shown. The project, considered time and again in subsequent centuries, was never carried out, but centuries later the express highway from Florence to the sea was built over the exact route Leonardo chose for his canal.

Also in 1503 Leonardo received a prized commission to paint a mural for the council hall in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio; a historical scene of monumental proportions (at 23 × 56 feet [7 × 17 metres], it would have been twice as large as the Last Supper). For three years he worked on this Battle of Anghiari; like its intended complementary painting, Michelangelo’s Battle of Cascina, it remained unfinished. During these same years Leonardo painted the Mona Lisa (c. 1503–19). (For more analysis of the work, see below The Mona Lisa and other works.)

The second Florentine period was also a time of intensive scientific study. Leonardo did dissections in the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova and broadened his anatomical work into a comprehensive study of the structure and function of the human organism. He made systematic observations of the flight of birds, about which he planned a treatise. Even his hydrological studies, “on the nature and movement of water,” broadened into research on the physical properties of water, especially the laws of currents, which he compared with those pertaining to air. These were also set down in his own collection of data, contained in the so-called Codex Hammer (formerly known as the Leicester Codex, now in the property of software entrepreneur Bill Gates in Seattle, Washington, U.S.).

Second Milanese period (1508–13)

In May 1506 Charles d’Amboise, the French governor in Milan, asked the Signoria in Florence if Leonardo could travel to Milan. The Signoria let Leonardo go, and the monumental Battle of Anghiari remained unfinished. Unsuccessful technical experiments with paints seem to have impelled Leonardo to stop working on the mural; one cannot otherwise explain his abandonment of this great work. In the winter of 1507–08 Leonardo went to Florence, where he helped the sculptor Giovanni Francesco Rustici execute his bronze statues for the Florence Baptistery, after which time he settled in Milan.

Last years (1513–19) of Leonardo da Vinci

In 1513 political events—the temporary expulsion of the French from Milan—caused the now 60-year-old Leonardo to move again. At the end of the year, he went to Rome, accompanied by his pupils Melzi and Salai as well as by two studio assistants, hoping to find employment there through his patron Giuliano de’ Medici, brother of the new pope, Leo X. Giuliano gave him a suite of rooms in his residence, the Belvedere, in the Vatican. He also gave Leonardo a considerable monthly stipend, but no large commissions followed. For three years Leonardo remained in Rome at a time of great artistic activity: Donato Bramante was building St. Peter’s, Raphael was painting the last rooms of the pope’s new apartments, Michelangelo was struggling to complete the tomb of Pope Julius II, and many younger artists, such as Timoteo Viti and Sodoma, were also active. Drafts of embittered letters betray the disappointment of the aging master, who kept a low profile while he worked in his studio on mathematical studies and technical experiments or surveyed ancient monuments as he strolled through the city. Leonardo seems to have spent time with Bramante, but the latter died in 1514, and there is no record of Leonardo’s relations with any other artists in Rome. A magnificently executed map of the Pontine Marshes suggests that Leonardo was at least a consultant for a reclamation project that Giuliano de’ Medici ordered in 1514. He also made sketches for a spacious residence to be built in Florence for the Medici, who had returned to power there in 1512. However, the structure was never built.

Sculpture of Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo worked as a sculptor from his youth on, as shown in his own statements and those of other sources. A small group of generals’ heads in marble and plaster, works of Verrocchio’s followers, are sometimes linked with Leonardo, because a lovely drawing attributed to him that is on the same theme suggests such a connection. But the inferior quality of this group of sculpture rules out an attribution to the master. No trace has remained of the heads of women and children that, according to Vasari, Leonardo modeled in clay in his youth.

The two great sculptural projects to which Leonardo devoted himself wholeheartedly were not realized; neither the huge, bronze equestrian statue for Francesco Sforza, on which he worked from about 1489 to 1494, nor the monument for Marshal Trivulzio, on which he was busy in the years 1506–11, were brought to completion. Many sketches of the work exist, but the most impressive were found in 1965 when two of Leonardo’s notebooks—the so-called Madrid Codices—were discovered in the National Library of Madrid. These notebooks reveal the sublimity but also the almost unreal boldness of his conception. Text and drawings both show Leonardo’s wide experience in the technique of bronze casting, but at the same time they reveal the almost utopian nature of the project. He wanted to cast the horse in a single piece, but the gigantic dimensions of the steed presented insurmountable technical problems. Indeed, Leonardo remained uncertain of the problem’s solution to the very end.

The drawings for these two monuments reveal the greatness of Leonardo’s vision of sculpture. Exact studies of the anatomy, movement, and proportions of a live horse preceded the sketches for the monuments; Leonardo even seems to have thought of writing a treatise on the horse. He pondered the merits of two positions for the horse—galloping or trotting—and in both commissions decided in favour of the latter. These sketches, superior in the suppressed tension of horse and rider to the achievements of Donatello’s statue of Gattamelata and Verrocchio’s statue of Colleoni, are among the most beautiful and significant examples of Leonardo’s art. Unquestionably—as ideas—they exerted a very strong influence on the development of equestrian statues in the 16th century.

Leonardo as artist-scientist

As the 15th century expired, Scholastic doctrines were in decline, and humanistic scholarship was on the rise. Leonardo, however, was part of an intellectual circle that developed a third, specifically modern, form of cognition. In his view, the artist—as transmitter of the true and accurate data of experience acquired by visual observation—played a significant part. In an era that often compared the process of divine creation to the activity of an artist, Leonardo reversed the analogy, using art as his own means to approximate the mysteries of creation, asserting that, through the science of painting, “the mind of the painter is transformed into a copy of the divine mind, since it operates freely in creating many kinds of animals, plants, fruits, landscapes, countrysides, ruins, and awe-inspiring places.” With this sense of the artist’s high calling, Leonardo approached the vast realm of nature to probe its secrets. His utopian idea of transmitting in encyclopaedic form the knowledge thus won was still bound up with medieval Scholastic conceptions; however, the results of his research were among the first great achievements of the forthcoming age’s thinking, because they were based to an unprecedented degree on the principle of experience.

Quotes

Total 45 Quotes

Life is pretty simple: You do some stuff. Most fails. Some works. You do more of what works.

Learning is the only thing the mind never exhausts, never fears, and never regrets.

Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.

Whatever you do in life, if you want to be creative and intelligent, and develop your brain, you must do everything with the awareness that everything, in some way, connects to everything else.

There are three classes of people: those who see, those who see when they are shown, those who do not see.

Experience is a truer guide than the words of others.

The greatest deception men suffer is from their own opinions.

It's not enough that you believe what you see. You must also understand what you see.

Be a mirror, absorb everything around you and still remain the same

To be a winner you must want to win but must know of the chance of losing and must not fear of it.