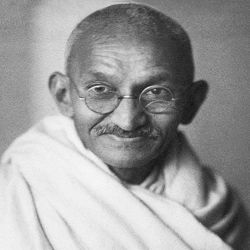

Mahatma Gandhi

Indian Lawyer, Anti-Colonial Nationalist and Political Ethicist

| Date of Birth | : | 02 Oct, 1869 |

| Date of Death | : | 30 Jan, 1948 |

| Place of Birth | : | Porbandar, India |

| Profession | : | Author, Politician, Political Campaigner |

| Nationality | : | Indian |

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist and political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British rule. He inspired movements for civil rights and freedom across the world.

Youth

Gandhi was the youngest child of his father’s fourth wife. His father—Karamchand Gandhi, who was the dewan (chief minister) of Porbandar, the capital of a small principality in western India (in what is now Gujarat state) under British suzerainty—did not have much in the way of a formal education. He was, however, an able administrator who knew how to steer his way between the capricious princes, their long-suffering subjects, and the headstrong British political officers in power.

Gandhi’s mother, Putlibai, was completely absorbed in religion, did not care much for finery or jewelry, divided her time between her home and the temple, fasted frequently, and wore herself out in days and nights of nursing whenever there was sickness in the family. Mohandas grew up in a home steeped in Vaishnavism—worship of the Hindu god Vishnu—with a strong tinge of Jainism, a morally rigorous Indian religion whose chief tenets are nonviolence and the belief that everything in the universe is eternal. Thus, he took for granted ahimsa (noninjury to all living beings), vegetarianism, fasting for self-purification, and mutual tolerance between adherents of various creeds and sects.

The educational facilities at Porbandar were rudimentary; in the primary school that Mohandas attended, the children wrote the alphabet in the dust with their fingers. Luckily for him, his father became dewan of Rajkot, another princely state. Though Mohandas occasionally won prizes and scholarships at the local schools, his record was on the whole mediocre. One of the terminal reports rated him as “good at English, fair in Arithmetic and weak in Geography; conduct very good, bad handwriting.” He was married at the age of 13 and thus lost a year at school. A diffident child, he shone neither in the classroom nor on the playing field. He loved to go out on long solitary walks when he was not nursing his by then ailing father (who died soon thereafter) or helping his mother with her household chores.

He had learned, in his words, “to carry out the orders of the elders, not to scan them.” With such extreme passivity, it is not surprising that he should have gone through a phase of adolescent rebellion, marked by secret atheism, petty thefts, furtive smoking, and—most shocking of all for a boy born in a Vaishnava family—meat eating. His adolescence was probably no stormier than that of most children of his age and class. What was extraordinary was the way his youthful transgressions ended.

“Never again” was his promise to himself after each escapade. And he kept his promise. Beneath an unprepossessing exterior, he concealed a burning passion for self-improvement that led him to take even the heroes of Hindu mythology, such as Prahlada and Harishcandra—legendary embodiments of truthfulness and sacrifice—as living models.

In 1887 Mohandas scraped through the matriculation examination of the University of Bombay (now University of Mumbai) and joined Samaldas College in Bhavnagar (Bhaunagar). As he had to suddenly switch from his native language—Gujarati—to English, he found it rather difficult to follow the lectures.

Meanwhile, his family was debating his future. Left to himself, he would have liked to have been a doctor. But, besides the Vaishnava prejudice against vivisection, it was clear that, if he was to keep up the family tradition of holding high office in one of the states in Gujarat, he would have to qualify as a barrister. That meant a visit to England, and Mohandas, who was not too happy at Samaldas College, jumped at the proposal. His youthful imagination conceived England as “a land of philosophers and poets, the very centre of civilization.” But there were several hurdles to be crossed before the visit to England could be realized. His father had left the family little property; moreover, his mother was reluctant to expose her youngest child to unknown temptations and dangers in a distant land. But Mohandas was determined to visit England. One of his brothers raised the necessary money, and his mother’s doubts were allayed when he took a vow that, while away from home, he would not touch wine, women, or meat. Mohandas disregarded the last obstacle—the decree of the leaders of the Modh Bania subcaste (Vaishya caste), to which the Gandhis belonged, who forbade his trip to England as a violation of the Hindu religion—and sailed in September 1888. Ten days after his arrival, he joined the Inner Temple, one of the four London law colleges (The Temple).

Sojourn in England and return to India of Mahatma Gandhi

Gandhi took his studies seriously and tried to brush up on his English and Latin by taking the University of London matriculation examination. But, during the three years he spent in England, his main preoccupation was with personal and moral issues rather than with academic ambitions. The transition from the half-rural atmosphere of Rajkot to the cosmopolitan life of London was not easy for him. As he struggled painfully to adapt himself to Western food, dress, and etiquette, he felt awkward. His vegetarianism became a continual source of embarrassment to him; his friends warned him that it would wreck his studies as well as his health. Fortunately for him he came across a vegetarian restaurant as well as a book providing a reasoned defense of vegetarianism, which henceforth became a matter of conviction for him, not merely a legacy of his Vaishnava background. The missionary zeal he developed for vegetarianism helped to draw the pitifully shy youth out of his shell and gave him a new poise. He became a member of the executive committee of the London Vegetarian Society, attending its conferences and contributing articles to its journal.

In the boardinghouses and vegetarian restaurants of England, Gandhi met not only food faddists but some earnest men and women to whom he owed his introduction to the Bible and, more important, the Bhagavadgita, which he read for the first time in its English translation by Sir Edwin Arnold. The Bhagavadgita (commonly known as the Gita) is part of the great epic the Mahabharata and, in the form of a philosophical poem, is the most-popular expression of Hinduism. The English vegetarians were a motley crowd. They included socialists and humanitarians such as Edward Carpenter, “the British Thoreau”; Fabians such as George Bernard Shaw; and Theosophists such as Annie Besant. Most of them were idealists; quite a few were rebels who rejected the prevailing values of the late-Victorian establishment, denounced the evils of the capitalist and industrial society, preached the cult of the simple life, and stressed the superiority of moral over material values and of cooperation over conflict. Those ideas were to contribute substantially to the shaping of Gandhi’s personality and, eventually, to his politics.

Painful surprises were in store for Gandhi when he returned to India in July 1891. His mother had died in his absence, and he discovered to his dismay that the barrister’s degree was not a guarantee of a lucrative career. The legal profession was already beginning to be overcrowded, and Gandhi was much too diffident to elbow his way into it. In the very first brief he argued in a court in Bombay (now Mumbai), he cut a sorry figure. Turned down even for the part-time job of a teacher in a Bombay high school, he returned to Rajkot to make a modest living by drafting petitions for litigants. Even that employment was closed to him when he incurred the displeasure of a local British officer. It was, therefore, with some relief that in 1893 he accepted the none-too-attractive offer of a year’s contract from an Indian firm in Natal, South Africa.

Years in South Africa

Africa was to present to Gandhi challenges and opportunities that he could hardly have conceived. In the end he would spend more than two decades there, returning to India only briefly in 1896–97. The youngest two of his four children were born there.

Emergence as a political and social activist

Gandhi was quickly exposed to the racial discrimination practiced in South Africa. In a Durban court he was asked by the European magistrate to take off his turban; he refused and left the courtroom. A few days later, while traveling to Pretoria, he was unceremoniously thrown out of a first-class railway compartment and left shivering and brooding at the rail station in Pietermaritzburg. In the further course of that journey, he was beaten up by the white driver of a stagecoach because he would not travel on the footboard to make room for a European passenger, and finally he was barred from hotels reserved “for Europeans only.” Those humiliations were the daily lot of Indian traders and labourers in Natal, who had learned to pocket them with the same resignation with which they pocketed their meagre earnings. What was new was not Gandhi’s experience but his reaction. He had so far not been conspicuous for self-assertion or aggressiveness. But something happened to him as he smarted under the insults heaped upon him. In retrospect the journey from Durban to Pretoria struck him as one of the most-creative experiences of his life; it was his moment of truth. Henceforth he would not accept injustice as part of the natural or unnatural order in South Africa; he would defend his dignity as an Indian and as a man.

While in Pretoria, Gandhi studied the conditions in which his fellow South Asians in South Africa lived and tried to educate them on their rights and duties, but he had no intention of staying on in South Africa. Indeed, in June 1894, as his year’s contract drew to a close, he was back in Durban, ready to sail for India. At a farewell party given in his honour, he happened to glance through the Natal Mercury and learned that the Natal Legislative Assembly was considering a bill to deprive Indians of the right to vote. “This is the first nail in our coffin,” Gandhi told his hosts. They professed their inability to oppose the bill, and indeed their ignorance of the politics of the colony, and begged him to take up the fight on their behalf.

Until the age of 18, Gandhi had hardly ever read a newspaper. Neither as a student in England nor as a budding barrister in India had he evinced much interest in politics. Indeed, he was overcome by a terrifying stage fright whenever he stood up to read a speech at a social gathering or to defend a client in court. Nevertheless, in July 1894, when he was barely 25, he blossomed almost overnight into a proficient political campaigner. He drafted petitions to the Natal legislature and the British government and had them signed by hundreds of his compatriots. He could not prevent the passage of the bill but succeeded in drawing the attention of the public and the press in Natal, India, and England to the Natal Indians’ grievances. He was persuaded to settle down in Durban to practice law and to organize the Indian community. In 1894 he founded the Natal Indian Congress, of which he himself became the indefatigable secretary. Through that common political organization, he infused a spirit of solidarity in the heterogeneous Indian community. He flooded the government, the legislature, and the press with closely reasoned statements of Indian grievances. Finally, he exposed to the view of the outside world the skeleton in the imperial cupboard, the discrimination practiced against the Indian subjects of Queen Victoria in one of her own colonies in Africa. It was a measure of his success as a publicist that such important newspapers as The Times of London and The Statesman and Englishman of Calcutta (now Kolkata) editorially commented on the Natal Indians’ grievances.

In 1896 Gandhi went to India to fetch his wife, Kasturba (or Kasturbai), and their two oldest children and to canvass support for the Indians overseas. He met prominent leaders and persuaded them to address public meetings in the country’s principal cities. Unfortunately for him, garbled versions of his activities and utterances reached Natal and inflamed its European population. On landing at Durban in January 1897, he was assaulted and nearly lynched by a white mob. Joseph Chamberlain, the colonial secretary in the British Cabinet, cabled the government of Natal to bring the guilty men to book, but Gandhi refused to prosecute his assailants. It was, he said, a principle with him not to seek redress of a personal wrong in a court of law.

Return to party leadership

During the mid-1920s Gandhi took little interest in active politics and was considered a spent force. In 1927, however, the British government appointed a constitutional reform commission under Sir John Simon, a prominent English lawyer and politician, that did not contain a single Indian. When the Congress and other parties boycotted the commission, the political tempo rose. At the Congress session (meeting) at Calcutta in December 1928, Gandhi put forth the crucial resolution demanding dominion status from the British government within a year under threat of a nationwide nonviolent campaign for complete independence. Henceforth, Gandhi was back as the leading voice of the Congress Party. In March 1930 he launched the Salt March, a satyagraha against the British-imposed tax on salt, which affected the poorest section of the community. One of the most spectacular and successful campaigns in Gandhi’s nonviolent war against the British raj, it resulted in the imprisonment of more than 60,000 people. A year later, after talks with the viceroy, Lord Irwin (later Lord Halifax), Gandhi accepted a truce (the Gandhi-Irwin Pact), called off civil disobedience, and agreed to attend the Round Table Conference in London as the sole representative of the Indian National Congress.

The conference, which concentrated on the problem of the Indian minorities rather than on the transfer of power from the British, was a great disappointment to the Indian nationalists. Moreover, when Gandhi returned to India in December 1931, he found his party facing an all-out offensive from Lord Irwin’s successor as viceroy, Lord Willingdon, who unleashed the sternest repression in the history of the nationalist movement. Gandhi was once more imprisoned, and the government tried to insulate him from the outside world and to destroy his influence. That was not an easy task. Gandhi soon regained the initiative. In September 1932, while still a prisoner, he embarked on a fast to protest against the British government’s decision to segregate the so-called “untouchables” (the lowest level of the Indian caste system; now called Scheduled Castes [official] or Dalits) by allotting them separate electorates in the new constitution. The fast produced an emotional upheaval in the country, and an alternative electoral arrangement was jointly and speedily devised by the leaders of the Hindu community and the Dalits and endorsed by the British government. The fast became the starting point of a vigorous campaign for the removal of the disenfranchisement of the Dalits, whom Gandhi referred to as Harijans, or “children of God.”

In 1934 Gandhi resigned not only as the leader but also as a member of the Congress Party. He had come to believe that its leading members had adopted nonviolence as a political expedient and not as the fundamental creed it was for him. In place of political activity he then concentrated on his “constructive programme” of building the nation “from the bottom up”—educating rural India, which accounted for 85 percent of the population; continuing his fight against untouchability; promoting hand spinning, weaving, and other cottage industries to supplement the earnings of the underemployed peasantry; and evolving a system of education best suited to the needs of the people. Gandhi himself went to live at Sevagram, a village in central India, which became the centre of his program of social and economic uplift.

The last phase

With the outbreak of World War II, the nationalist struggle in India entered its last crucial phase. Gandhi hated fascism and all it stood for, but he also hated war. The Indian National Congress, on the other hand, was not committed to pacifism and was prepared to support the British war effort if Indian self-government was assured. Once more Gandhi became politically active. The failure of the mission of Sir Stafford Cripps, a British cabinet minister who went to India in March 1942 with an offer that Gandhi found unacceptable, the British equivocation on the transfer of power to Indian hands, and the encouragement given by high British officials to conservative and communal forces promoting discord between Muslims and Hindus impelled Gandhi to demand in the summer of 1942 an immediate British withdrawal from India—what became known as the Quit India Movement.

In mid-1942 the war against the Axis powers, particularly Japan, was in a critical phase, and the British reacted sharply to the campaign. They imprisoned the entire Congress leadership and set out to crush the party once and for all. There were violent outbreaks that were sternly suppressed, and the gulf between Britain and India became wider than ever before. Gandhi, his wife, and several other top party leaders (including Nehru) were confined in the Aga Khan Palace (now the Gandhi National Memorial) in Poona (now Pune). Kasturba died there in early 1944, shortly before Gandhi and the others were released.

A new chapter in Indo-British relations opened with the victory of the Labour Party in Britain 1945. During the next two years, there were prolonged triangular negotiations between leaders of the Congress, the Muslim League under Mohammed Ali Jinnah, and the British government, culminating in the Mountbatten Plan of June 3, 1947, and the formation of the two new dominions of India and Pakistan in mid-August 1947.

It was one of the greatest disappointments of Gandhi’s life that Indian freedom was realized without Indian unity. Muslim separatism had received a great boost while Gandhi and his colleagues were in jail, and in 1946–47, as the final constitutional arrangements were being negotiated, the outbreak of communal riots between Hindus and Muslims unhappily created a climate in which Gandhi’s appeals to reason and justice, tolerance and trust had little chance. When partition of the subcontinent was accepted—against his advice—he threw himself heart and soul into the task of healing the scars of the communal conflict, toured the riot-torn areas in Bengal and Bihar, admonished the bigots, consoled the victims, and tried to rehabilitate the refugees. In the atmosphere of that period, surcharged with suspicion and hatred, that was a difficult and heartbreaking task. Gandhi was blamed by partisans of both the communities. When persuasion failed, he went on a fast. He won at least two spectacular triumphs: in September 1947 his fasting stopped the rioting in Calcutta, and in January 1948 he shamed the city of Delhi into a communal truce. A few days later, on January 30, while he was on his way to his evening prayer meeting in Delhi, he was shot down by Nathuram Godse, a young Hindu fanatic.

Quotes

Total 50 Quotes

There are two days in the year that we can not do anything, yesterday and tomorrow

Carefully watch your thoughts, for they become your words. Manage and watch your words, for they will become your actions. Consider and judge your actions, for they have become your habits. Acknowledge and watch your habits, for they shall become your values. Understand and embrace your values, for they become your destiny.

Relationships are based on four principles: respect, understanding, acceptance and appreciation.

All good thoughts and ideas mean nothing without action

Our greatest ability as humans is not to change the world; but to change ourselves.

The true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most vulnerable members

Many people, especially ignorant people, want to punish you for speaking the truth, for being correct, for being you. Never apologize for being correct, or for being years ahead of your time. If you’re right and you know it, speak your mind. Speak your mind. Even if you are a minority of one, the truth is still the truth.

it's easy to stand in the crowd but it takes courage to stand alone

Keep your thoughts positive because your thoughts become your words. Keep your words positive because your words become your behavior. Keep your behavior positive because your behavior becomes your habits. Keep your habits positive because your habits become your values. Keep your values positive because your values become your destiny.

You never know where your actions will lead to. But if you don't do anything they will lead you nowhere.