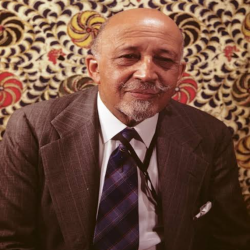

W. E. B. Du Bois

American Sociologist

| Date of Birth | : | 23 Feb, 1868 |

| Date of Death | : | 27 Aug, 1963 |

| Place of Birth | : | Great Barrington, Massachusetts, United States |

| Profession | : | Sociologist |

| Nationality | : | American |

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relatively tolerant and integrated community.

The Souls of Black Folk, the Niagara Movement, and the NAACP

Du Bois graduated from Fisk University, a historically Black institution in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1888. He received a Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1895. His doctoral dissertation, The Suppression of the African Slave-Trade to the United States of America, 1638–1870, was published in 1896. Although Du Bois took an advanced degree in history, he was broadly trained in the social sciences; and, at a time when sociologists were theorizing about race relations, he was conducting empirical inquiries into the condition of Blacks. For more than a decade he devoted himself to sociological investigations of Blacks in America, producing 16 research monographs published between 1897 and 1914 at Atlanta University in Georgia, where he was a professor, as well as The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study (1899), the first case study of a Black community in the United States.

Two years later, in 1905, Du Bois took the lead in founding the Niagara Movement, which was dedicated chiefly to attacking the platform of Booker T. Washington. The small organization, which met annually until 1909, was seriously weakened by internal squabbles and Washington’s opposition. But it was significant as an ideological forerunner and direct inspiration for the interracial NAACP, founded in 1909. Du Bois played a prominent part in the creation of the NAACP and became the association’s director of research and editor of its magazine, The Crisis. In this role he wielded an unequaled influence among middle-class Blacks and progressive whites as the propagandist for the Black protest from 1910 until 1934.

Both in the Niagara Movement and in the NAACP, Du Bois acted mainly as an integrationist, but his thinking always exhibited, to varying degrees, separatist-nationalist tendencies. In The Souls of Black Folk he had expressed the characteristic dualism of Black Americans:

Black nationalism and later works

Du Bois’s Black nationalism took several forms—the most influential being his pioneering advocacy of Pan-Africanism, the belief that all people of African descent had common interests and should work together in the struggle for their freedom. Du Bois was a leader of the first Pan-African Conference in London in 1900 and the architect of four Pan-African Congresses held between 1919 and 1927. Second, he articulated a cultural nationalism. As the editor of The Crisis, he encouraged the development of Black literature and art and urged his readers to see “Beauty in Black.” Third, Du Bois’s Black nationalism is seen in his belief that Blacks should develop a separate “group economy” of producers’ and consumers’ cooperatives as a weapon for fighting economic discrimination and Black poverty. This doctrine became especially important during the economic catastrophe of the 1930s and precipitated an ideological struggle within the NAACP.

He resigned from the editorship of The Crisis and the NAACP in 1934, yielding his influence as a race leader and charging that the organization was dedicated to the interests of the Black bourgeoisie and ignored the problems of the masses. Du Bois’s interest in cooperatives was a part of his nationalism that developed out of his Marxist leanings. At the turn of the century, he had been an advocate of Black capitalism and Black support of Black business, but by about 1905 he had been drawn toward socialist doctrines. Although he joined the Socialist Party only briefly in 1912, he remained sympathetic with Marxist ideas throughout the rest of his life.

Upon leaving the NAACP, he returned to Atlanta University, where he devoted the next 10 years to teaching and scholarship. In 1940 he founded the magazine Phylon, Atlanta University’s “Review of Race and Culture.” In 1945 he published the “Preparatory Volume” of a projected Encyclopedia Africana, for which he had been appointed editor in chief and toward which he had been working for decades. He also produced two major books during this period. Black Reconstruction: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880 (1935) was an important Marxist interpretation of Reconstruction (the period following the American Civil War during which the seceded Southern states were reorganized according to the wishes of Congress), and, more significantly, it provided the first synthesis of existing knowledge of the role of Blacks in that critical period of American history. In 1940 appeared Dusk of Dawn, subtitled An Essay Toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept. In this brilliant book, Du Bois explained his role in both the African and the African American struggles for freedom, viewing his career as an ideological case study illuminating the complexity of the Black-white conflict.

Following this fruitful decade at Atlanta University, he returned once more to a research position at the NAACP (1944–48). This brief connection ended in a second bitter quarrel, and thereafter Du Bois moved steadily leftward politically. Identified with pro-Russian causes, he was indicted in 1951 as an unregistered agent for a foreign power. Although a federal judge directed his acquittal, Du Bois had become completely disillusioned with the United States. In 1961 he applied to, and was accepted as a member of, the Communist Party. That same year he left the United States for Ghana, where he began work on the Encyclopedia Africana in earnest, though it would never be completed, and where he later became a citizen.

Du Bois also wrote several novels, including the trilogy The Black Flame (1957–61). The Autobiography of W.E.B. Du Bois was published in the United States in 1968.

Quotes

Total 50 Quotes

The emancipation of man is the emancipation of labor and the emancipation of labor is the freeing of that basic majority of workers who are yellow, brown and black.

Oppression costs the oppressor too much if the oppressed stands up and protests. The protest need not be merely physical-the throwing of stones and bullets-if it is mental, spiritual; if it expresses itself in silent, persistent dissatisfaction, the cost to the oppressor is terrific.

The favorite device of the devil, ancient and modern, is to force a human being into a more or less artificial class, accuse the class of unnamed and unnameable sin, and then damn any individual in the alleged class, however innocent he may be.

Most men in this world are colored. A belief in humanity means a belief in colored men. The future world will, in all reasonable probability, be what colored men make it.

The future woman must have a life work and economic independence. She must have the right of motherhood at her own discretion.

Most men today cannot conceive of a freedom that does not involve somebody's slavery.

We cannot escape the clear fact that what is going to win in this world is reason, if this ever becomes a reasonable world.

The cause of war is preparation for war.

There can be no perfect democracy curtailed by color, race, or poverty. But with all we accomplish all, even peace.

A man does not look behind the door unless he has stood there himself