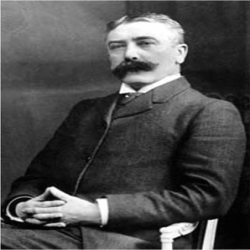

Ferdinand de Saussure

Swiss linguist

| Date of Birth | : | 26 Nov, 1856 |

| Date of Death | : | 22 Feb, 1913 |

| Place of Birth | : | Geneva, Switzerland |

| Profession | : | Educationalist, Philosopher, Linguist, Sociologist |

| Nationality | : | Swiss |

Ferdinand de Saussure was a Swiss linguist, semiotician and philosopher. His ideas laid the foundation for many significant developments in both linguistics and semiotics in the 20th century. He is widely considered a founder of twentieth-century linguistics and one of the two main founders (along with Charles Sanders Peirce) of semiotics, or semiology, as Saussure called it.

One of his translators, Roy Harris, summarized Saussure's contribution to linguistics and "the study of the whole range of human sciences. It is especially marked in linguistics, philosophy, psychoanalysis, psychology, sociology and anthropology." Although they have undergone expansion and critique over time, the dimensions of organization introduced by Saussure continue to inform contemporary approaches to the phenomenon of language. As Leonard Bloomfield said after reviewing the courses: "He gave us the theoretical foundations of the science of human speech".

Biography

Saussure was born in Geneva in 1857. His father, Henri Louis Frédéric de Saussure, was a mineralogist, entomologist, and taxonomist. Saussure showed signs of considerable talent and intellectual ability as early as the age of fourteen. In the autumn of 1870, he began attending the Institution Martine (previously the Institution Lecoultre until 1969), in Geneva. There he lived with the family of a classmate, Elie David. After graduating at the top of class, Saussure expected to continue his studies at the Gymnase de Genève, but his father decided he was not mature enough at fourteen and a half, and sent him to the Collège de Genève instead. Saussure was not pleased, as he complained: "I entered the Collège de Genève, to waste a year there as completely as a year can be wasted."

After a year of studying Latin, Ancient Greek, and Sanskrit and taking a variety of courses at the University of Geneva, he commenced graduate work at the University of Leipzig in 1876.

Two years later, at 21, Saussure published a book entitled Mémoire sur le système primitif des voyelles dans les langues indo-européennes (Dissertation on the Primitive Vowel System in Indo-European Languages). After this, he studied for a year at the University of Berlin under the Privatdozent Heinrich Zimmer, with whom he studied Celtic and Hermann Oldenberg with whom he continued his studies of Sanskrit. He returned to Leipzig to defend his doctoral dissertation De l'emploi du génitif absolu en Sanscrit, and was awarded his doctorate in February 1880. Soon, he relocated to the University of Paris, where he lectured on Sanskrit, Gothic, Old High German, and occasionally other subjects.

Ferdinand de Saussure is one of the world's most quoted linguists, which is remarkable as he hardly published anything during his lifetime. Even his few scientific articles are not unproblematic. Thus, for example, his publication on Lithuanian phonetics is mostly taken from studies by the Lithuanian researcher Friedrich Kurschat, with whom Saussure traveled through Lithuania in August 1880 for two weeks and whose (German) books Saussure had read. Saussure, who had studied some basic grammar of Lithuanian in Leipzig for one semester but was unable to speak the language, was thus dependent on Kurschat.

Work and influence

Saussure's theoretical reconstructions of the Proto-Indo-European language vocalic system and particularly his theory of laryngeals, otherwise unattested at the time, bore fruit and found confirmation after the decipherment of Hittite in the work of later generations of linguists such as Émile Benveniste and Walter Couvreur, who both drew direct inspiration from their reading of the 1878 Mémoire.

Saussure had a major impact on the development of linguistic theory in the first half of the 20th century with his notions becoming incorporated in the central tenets of structural linguistics. His main contribution to structuralism was his theory of a two-tiered reality about language. The first is the langue, the abstract and invisible layer, while the second, the parole, refers to the actual speech that we hear in real life. This framework was later adopted by Claude Levi-Strauss, who used the two-tiered model to determine the reality of myths. His idea was that all myths have an underlying pattern, which forms the structure that makes them myths.

In America, where the term 'structuralism' became highly ambiguous, Saussure's ideas informed the distributionalism of Leonard Bloomfield, but his influence remained limited. Systemic functional linguistics is a theory considered to be based firmly on the Saussurean principles of the sign, albeit with some modifications. Ruqaiya Hasan describes systemic functional linguistics as a 'post-Saussurean' linguistic theory. Michael Halliday argues:

Saussure took the sign as the organizing concept for linguistic structure, using it to express the conventional nature of language in the phrase "l'arbitraire du signe". This has the effect of highlighting what is, in fact, the one point of arbitrariness in the system, namely the phonological shape of words, and hence allows the non-arbitrariness of the rest to emerge with greater clarity. An example of something that is distinctly non-arbitrary is the way different kinds of meaning in language are expressed by different kinds of grammatical structure, as appears when linguistic structure is interpreted in functional terms.

Course in General Linguistics

Saussure's most influential work, Course in General Linguistics (Cours de linguistique générale), was published posthumously in 1916 by former students Charles Bally and Albert Sechehaye, based on notes taken from Saussure's lectures in Geneva. The Course became one of the seminal linguistics works of the 20th century not primarily for the content (many of the ideas had been anticipated in the works of other 20th-century linguists) but for the innovative approach that Saussure applied in discussing linguistic phenomena.

Its central notion is that language may be analyzed as a formal system of differential elements, apart from the messy dialectics of real-time production and comprehension. Examples of these elements include his notion of the linguistic sign, which is composed of the signifier and the signified. Though the sign may also have a referent, Saussure took that to lie beyond the linguist's purview.

Laryngeal theory

While a student, Saussure published an important work about Proto-Indo-European, which explained unusual forms of word roots in terms of lost phonemes he called sonant coefficients. The Scandinavian scholar Hermann Möller suggested that they might be laryngeal consonants, leading to what is now known as the laryngeal theory. After Hittite texts were discovered and deciphered, Polish linguist Jerzy Kuryłowicz recognized that a Hittite consonant stood in the positions where Saussure had theorized a lost phoneme some 48 years earlier, confirming the theory. It has been argued that Saussure's work on this problem, systematizing the irregular word forms by hypothesizing then-unknown phonemes, stimulated his development of structuralism.

Influence outside linguistics

The principles and methods employed by structuralism were later adapted in diverse fields by French intellectuals such as Roland Barthes, Jacques Lacan, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, and Claude Lévi-Strauss. Such scholars took influence from Saussure's ideas in their areas of study (literary studies/philosophy, psychoanalysis, anthropology, etc.).

View of language

Saussure approaches the theory of language from two different perspectives. On the one hand, language is a system of signs. That is, a semiotic system; or a semiological system as he calls it. On the other hand, a language is also a social phenomenon: a product of the language community.

Language as semiology

The bilateral sign

One of Saussure's key contributions to semiotics lies in what he called semiology, the concept of the bilateral (two-sided) sign which consists of 'the signifier' (a linguistic form, e.g. a word) and 'the signified' (the meaning of the form). Saussure supported the argument for the arbitrariness of the sign although he did not deny the fact that some words are onomatopoeic, or claim that picture-like symbols are fully arbitrary. Saussure also did not consider the linguistic sign as random, but as historically cemented. All in all, he did not invent the philosophy of arbitrariness but made a very influential contribution to it.

The arbitrariness of words of different languages itself is a fundamental concept in Western thinking of language, dating back to Ancient Greek philosophers. The question of whether words are natural or arbitrary (and artificially made by people) returned as a controversial topic during the Age of Enlightenment when the medieval scholastic dogma, that languages were created by God, became opposed by the advocates of humanistic philosophy. There were efforts to construct a 'universal language', based on the lost Adamic language, with various attempts to uncover universal words or characters which would be readily understood by all people regardless of their nationality. John Locke, on the other hand, was among those who believed that languages were a rational human innovation, and argued for the arbitrariness of words.

Language as a social phenomenon

In his treatment of language as a 'social fact', Saussure touches on topics that were controversial in his time, and that would continue to split opinions in the post-war structuralist movement. Saussure's relationship with 19th-century theories of language was somewhat ambivalent. These included social Darwinism and Völkerpsychologie or Volksgeist thinking which were regarded by many intellectuals as nationalist and racist pseudoscience.

Saussure, however, considered the ideas useful if treated properly. Instead of discarding August Schleicher's organicism or Heymann Steinthal's "spirit of the nation", he restricted their sphere in ways that were meant to preclude any chauvinistic interpretations.

Organic analogy

Saussure exploited the sociobiological concept of language as a living organism. He criticises August Schleicher and Max Müller's ideas of languages as organisms struggling for living space but settles with promoting the idea of linguistics as a natural science as long as the study of the 'organism' of language excludes its adaptation to its territory. This concept would be modified in post-Saussurean linguistics by the Prague circle linguists Roman Jakobson and Nikolai Trubetzkoy and eventually diminished.

The speech circuit

Perhaps the most famous of Saussure's ideas is the distinction between language and speech (Fr. langue et parole), with 'speech' referring to the individual occurrences of language usage. These constitute two parts of three of Saussure's 'speech circuit' (circuit de parole). The third part is the brain, that is, the mind of the individual member of the language community. This idea is in principle borrowed from Steinthal, so Saussure's concept of a language as a social fact corresponds to "Volksgeist", although he was careful to preclude any nationalistic interpretations. In Saussure's and Durkheim's thinking, social facts and norms do not elevate the individuals but shackle them. Saussure's definition of language is statistical rather than idealised.

"Among all the individuals that are linked together by speech, some sort of average will be set up : all will reproduce — not exactly of course, but approximately — the same signs united with the same concepts."

Saussure versus the social Darwinists

Saussure's Course in General Linguistics begins and ends with a criticism of 19th-century linguistics where he is especially critical of Volkgeist thinking and the evolutionary linguistics of August Schleicher and his colleagues. Saussure's ideas replaced social Darwinism in Europe as it was banished from humanities at the end of World War II.

The publication of Richard Dawkins's memetics in 1976 brought the Darwinian idea of linguistic units as cultural replicators back to vogue. It became necessary for adherents of this movement to redefine linguistics in a way that would be simultaneously anti-Saussurean and anti-Chomskyan. This led to a redefinition of old humanistic terms such as structuralism, formalism, functionalism, and constructionism along Darwinian lines through debates that were marked by an acrimonious tone. In a functionalism–formalism debate of the decades following The Selfish Gene, the 'functionalism' camp attacking Saussure's legacy includes frameworks such as Cognitive Linguistics, Construction Grammar, Usage-based linguistics, and Emergent Linguistics. Arguing for 'functional-typological theory', William Croft criticises Saussure's use of the organic analogy:

When comparing functional-typological theory to biological theory, one must take care to avoid a caricature of the latter. In particular, in comparing the structure of language to an ecosystem, one must not assume that in contemporary biological theory, it is believed that an organism possesses a perfect adaptation to a stable niche inside an ecosystem in equilibrium. The analogy of a language as a perfectly adapted 'organic' system where tout se tient is a characteristic of the structuralist approach, and was prominent in early structuralist writing. The static view of adaptation in biology is not tenable in the face of empirical evidence of nonadaptive variation and competing adaptive motivations of organisms.

Structural linguist Henning Andersen disagrees with Croft. He criticises memetics and other models of cultural evolution and points out that the concept of 'adaptation' is not to be taken in linguistics in the same meaning as in biology. Humanistic and structuralistic notions are likewise defended by Esa Itkonen and Jacques François; the Saussurean standpoint is explained and defended by Tomáš Hoskovec, representing the Prague Linguistic Circle.

Quotes

Total 29 Quotes

Without language, thought is a vague, uncharted nebula.

The connection between the signifier and the signified is arbitrary.

The ultimate law of language is, dare we say, that nothing can ever reside in a single term. This is a direct consequence of the fact that linguistic signs are unrelated to what they designate and that, therefore, 'a' cannot designate anything without the the aid of 'b' and vice versa, or, in other words, that both have value only by the difference between them.

Time changes all things; there is no reason why language should escape this universal law.

I’m almost never serious, and I’m always too serious. Too deep, too shallow. Too sensitive, too cold hearted. I’m like a collection of paradoxes.

A linguistic system is a series of differences of sound combined with a series of differences of ideas.

Speech has both an individual and a social side, and we cannot conceive of one without the other.

Language furnishes the best proof that a law accepted by a community is a thing that is tolerated and not a rule to which all freely consent.

In the lives of individuals and societies, language is a factor of greater importance than any other. For the study of language to remain solely the business of a handful of specialists would be a quite unacceptable state of affairs.

Written forms obscure our view of language. They are not so much a garment as a disguise.